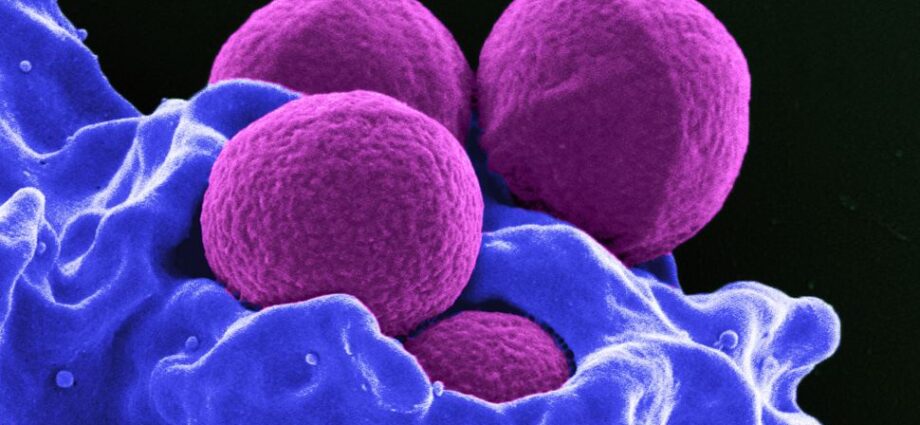

By definition, microbes are supposed to be so small they can only be seen with a microscope. But a newly described bacterium living in Caribbean mangroves never got that memo (see video, above). Its threadlike single cell is visible to the naked eye, growing up to 2 centimeters—as long as a peanut—and 5000 times bigger than many other microbes. What’s more, this giant has a huge genome that’s not free floating inside the cell as in other bacteria, but is instead encased in a membrane, an innovation characteristic of much more complex cells, like those in the human body.

The bacterium was unveiled in a preprint posted online last week and it has astounded some researchers who have reviewed its features. “When it comes to bacteria, I never say never, but this one for sure is pushing what we thought was the upper limit [of size] by 10-fold,” says Verena Carvalho, a microbiologist at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

The discovery is “fantastic and eye-opening,” adds Victor Nizet, a physician scientist at the University of California, San Diego, who studies infectious diseases. The oversize bacterium is bigger than fruit flies and nematodes, common lab organisms that he and others sometimes infect with much smaller bacteria for their research.

Aside from upending ideas about how big—and sophisticated—microbes can become, this bacterium “could be a missing link in the evolution of complex cells,” says Kazuhiro Takemoto, a computational biologist at the Kyushu Institute of Technology.

Researchers have long divided life into two groups: prokaryotes, which include bacteria and single-cell microbes called archaea, and eukaryotes, which include everything from yeast to most forms of multicellular life, including humans. Prokaryotes have free-floating DNA, whereas eukaryotes package their DNA in a nucleus. Eukaryotes also compartmentalize various cell functions into vesicles called organelles and can move molecules from one compartment to another—something prokaryotes can’t.

But the newly discovered microbe blurs the line between prokaryotes and eukaryotes. About 10 years ago, Olivier Gros, a marine biologist at the University of the French Antilles, Pointe-à-Pitre, came across the strange organism growing as thin filaments on the surfaces of decaying mangrove leaves in a local swamp. Not until 5 years later did he and his colleagues realize the organisms were actually bacteria. And they didn’t appreciate how special the microbes were until more recently, when Gros’s graduate student Jean-Marie Volland took up the challenge of trying to characterize them.

By Elizabeth Pennisi

https://www.science.org